Also published on

Cinescene.

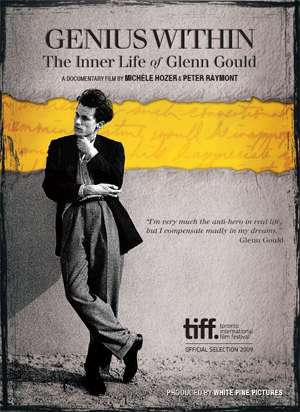

Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould

Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould Glenn Gould, the singular Canadian pianist and writer who died in 1982, was a musical genius whose contribution is still important and always will be. This new film about him is one of many, but it may be the most comprehensive, emotionally warm, and exciting of all the on screen portraits, and for both those who already love him and newcomers who want to learn, it's essential viewing.

The many existing films of this most documented of musical figures include the 1985 documentary

Glenn Gould: A Portrait and François Girard's flavorful if fanciful 1993

Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould. Nothing explores Gould's filmed playing, TV appearances, and radio work as thoroughly as Bruno Monsaingeon's worshipful and erudite films, including the 13-part CBC miniseries "The Glenn Gould Collection." This new documentary, Hozer and Raymont's

Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould is a beautiful tribute containing the fruits of several thoroughly researched biographies and new interviews and giving a joyous sense of his glamour and personal appeal, especially as a young man. It's full of archival footage and sound so brilliantly and seamlessly edited you feel Glenn Gould is alive and talking to you today.

Genius Within is especially good at celebrating the charm and youthful good looks of the twenty-something keyboard master, building on early archival material and the films shot when he made his first recordings at Columbia.

A prodigy, born in 1932, Glenn graduated from the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto with highest honors at 13 and began public performance at 14. In 1955, at the age of 23, he made a recording of Bach's

Goldberg Variations for Columbia Records that made him instantly famous. The lean precision, the energy, the keen intelligence, the effortless fluency, the balance of the left and right hands, the rhythmic muscularity, the clear separation of thematic lines, were unmatched; the style was instantly recognizable and was to remain so. A sample of his

Well Tempered Clavier has been sent into outer space to show other beings what us humans are capable of. Here on earth Sony has reissued all his recordings and they are much listened to. He first became famous for his eccentricities, whose value for selling his records he came to understand. A

Life Magazine article showed him bundled up in overcoat, gloves and scarf in warm weather and soaking his hands and arms in hot water before playing, and these practices, along with robust baritone vocalizing when he played, continued all his life, as did nocturnal habits, isolation, and hypochondria and control-freak tendencies whenever he recorded or edited -- tendencies about which, however, he was always cheerful and good-natured. Making friends was never easy for Glenn, but many came to love him, and some of these are essential talking heads newly heard from in

Genius Within. When he died, thousands came to his memorial in the Anglican cathedral in Toronto and many wept when the strains of the Aria from the Goldberg (one lover laughingly calls it the "Gouldberg") Variations were heard.

Gould is a complex subject, but this film feels thorough. For every period of the life there seems to be more archival footage, more smoothly introduced than ever before. Family, childhood, school, musical training are well developed. A newly clarified point: his radically low seat at the piano (the eccentric sawed-off chair carried everywhere) and his staccato close-to-the-key touch were both techniques rigorously taught to all the students of Gould's main piano teacher at the Conservatory, Alberto Guerrero; Gould simply mastered them more thoroughly than the other students and made them more completely his own. This film brings certain moments to life as never before, such as the several weeks of his early tour of Russia, where he made an immense impression, as Vladimir Ashkenazy comments. There's not much that's not well covered here. And there's material that's almost completely new, notably the exploration of Gould's love life. Through the use of films of Glenn playing there is a fine sense of the uniqueness, seeming perfection, and hypnotic intensity of his early performances, especially of Bach. Many stills show his good looks and charm as a young man.

A major dividing line comes in 1964 when, at 32, after only eleven years of big-time international concert touring, Glenn carried out a threat of some years and formally quit giving public concerts altogether to devote himself to recording. He was always shy, rather a recluse, and he detested the cruel "blood sport" aspect of public performances. That any particular conflict, such as Leonard Bernstein's somewhat grandstanding pubic declaration of differing from Glenn on his ultra-slow first movement tempo in Brahms' Piano Concerto No. 1, caused Glenn's departure from the stage, seems unlikely; in this film he's even heard saying Bernstein's speech amused and charmed him and it probably did. With time free from touring, he focused on recording, but also on his unique radio creations, beginning with "The Idea of North," and many TV performances and talks, and comedy turns where he showed his penchant for somewhat silly collegiate humor, as well as a love of the songs of Petula Clark, who, in an interview, wishes they'd gotten together.

The myth that Gould was a weird recluse is shattered in this film's exploration of his straightforward heterosexual relationships with various women -- most notably with Cornelia Foss, wife of composer and pianist Lucas Foss, who left her husband and went to live in Toronto with her son and daughter to be with Gould for four and a half years. She only made public this relationship in 2007. Here she and the grown son and daughter speak freely about Gould's important role in their lives. He loved animals, but he also was great with children, Cornelia reveals. True, she admits her lover's eccentricities, including a disturbing paranoid tendency, grew greater than when they met and led, sadly for both and for the children, to a breakup and gradual return to her husband, but this story shows Gould's dark, eccentric side is partly a myth he himself encouraged than the reality.Before Cornelia there was a musical contemporary, fleetingly interviewed. After, there was an opera singer he worked with, Roxolana Roslak, who became his companion.

The focus on all this is essential in humanizing the famous eccentric, but there is a corresponding gap. The film doesn't fully chronicle Gould's serious achievements during the 18 years of post-concertizing work life before his sadly premature death, long predicted by him, at 50. There's no mention of his many essays and polemics and no full review of his TV work. Most importantly, this film doesn't provide much of an idea of the range of his recordings. His discs of all the keyboard music of Bach are his greatest monument, but there is plenty more. Though he eschewed the romantics, playing only Liszt's "deorchestrations" of the Beethoven symphonies, and not much Schumann, Schubert, or Chopin, he did record Brahms and Beethoven in generous quantities and a controversial set of all Mozart's piano sonatas and less controversial one of all Haydn's. He had a strong penchant for atonal modern music of Schoenberg, Berg, Krenek, et al., and he was a great lover of Richard Strauss. Since recording was his refuge, a bit more detail about what he did there was in order (see Montsaingeon's films). Gould'slimited output as a composer isn't completely described either, though it comes in for mention early and his "So You Want to Write a Fugue" choral fugue is the closing credit music.

What is thoroughly explored is Glenn's involvement in sound engineering, with his intimate friend and collaborator the engineer Lorne Tulk the main spokesman about that, and Tulk's moving contribution makes up for a lot.

It's true, and not true, that Gould was a "James Dean" or "Michael Jackson" of classical music. It's true that his eccentricities (and charm too) explain why he has been so thoroughly documented and written about. But even if he played for the camera, his eccentricities were also real. And though they may explain some of his fame, his Bach speaks for itself and always will. Once you get past the eccentricities, what remains is greatness. Hopefully this film will lead more to more people appreciating Gould's manifold gifts.

The young Glenn Gould playing Bach

The young Glenn Gould playing Bach