Films of the Radical Saint: Mr. de Antonio and I

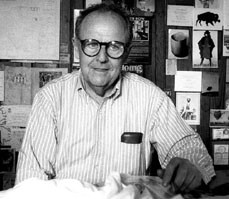

Films of the Radical Saint: Mr. de Antonio and IMy father once taught at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. One night when I was eight or nine he gave a party at our house on Capital Landing Road and a young colleague got drunk and drove his car through the big piece of canvas stretched over our driveway that I used as a tent. His wife came back and got the canvas later and sewed it back together, but I felt my refuge had been violated, and always thought of that guy, from my point of view as a little boy whose tent got wrecked, as a very bad man. My father called him "de Antonio." His first name was Emile. It was an unusual name. I never forgot it. I gather that from my father's point of view, he was a good drinking companion, someone he used to talk about.

Many years later I heard about an Emile de Antonio who had become a legendary radical leftist documentary filmmaker. To my surprise he turned out to be the same man my father used to know. If you hunt around in his

biography it's there: for a couple of years De Antonio, the filmmaker, taught English and philosophy at William and Mary. In later years his friends and his six wives called him "De." In the last year of his life, 1989, he still said that he drank too much. He said that in

Mr. Hoover and I, released in that final year, a kind of credo and brief autobiography along with a statement about J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI, and freedom and politics in the United States of America, a country for which he declares his love. If you watch this film you will understand what a sterling character this drunken driver was, and you'll understand why the book

Necessary Illusions (1989) by Noam Chomsky and the documentary

Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media (1992) by Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick are dedicated to Emile de Antonio.

"De" ultimately made a series of films about government, war, and dissent that made him famous. He was a late bloomer: he didn't begin his most important work until he was 43 years old. But his twenty-plus years of documentary filmmaking constitutes an essential body of film statements about the central issues of American politics in the Cold War era. The most notable ones are:

Point of Order (1964, about Senator Joseph McCarthy and McCarthyism),

Rush to Judgment (1966, about the JFK assassination),

In the Year of the Pig (1968, about the Vietnam War),

Millhouse: A White Comedy (1971, about Nixon),

Painters Painting (1972, about the New York art scene),

Underground (1976, about the Weather Underground), and his personal summation,

Mr. Hoover and I. Most of these films are readily available now on DVD, four of them in a set (see above), entitled "Films of the Radical Saint."

When De Antonio went to New York after Virginia he seems to have drifted for over a decade, living by his wits. He's said to have gotten involved in various get-rich schemes. He also laid a rich groundwork of connections. He made many friends, including the art crowd, the abstract expressionists and their successors, Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg, John Cage, Andy Warhol, and many others, whom he helped when they were getting started -- including Jonas Mekas and avant garde filmmakers of the Fifties and Sixties. Thus he distributed Robert Frank's beat film

Pull My Daisy. He knew a lot of wealthy people with liberal-leftist views whom he was later able to persuade to fund his films. Like Christo and Jeanne Claude, he avoided being beholden to foundations and grants. "De" had graduated from Harvard (a good cource of connections), where my father studied for a time; but de Antonio entered Harvard at sixteen, some years after my father studied there. "De's" father was a wealthy Italian doctor who had co-owned a hospital in Italy. He grew up in a big house in Scranton, Pennsylvania with a live-in maid and cook and a driver. "I came from a background of privilege, people with money. And people with money put up the money for my films. I never applied to the Foundations or the networks," he told Bruce Jackson in a running

interview reproduced in

Senses of Cinema. Mostly

Mr. Hoover and I (1989, 86 min.), his last film and my first introduction to the man and his work, is de Antonio talking to the camera -- in fact he always thought of his films as words first, and pictures later. He's also shown giving a large lecture at Dartmouth, talking while having his hair cut by his wife Nancy, and chatting with John Cage ( dear friend and also a major influence) in Cage's kitchen in New York. Toward the end of

Mr. Hoover and I De Antonio eloquently states why he feels documentary filmmaking is a beautiful and important form in which to work. Integral to his sense of the essential nature of documentary is his special definition of the word "politics." For him it always primarily meant working for social change -- a definition, and a process, he says in the film, was crushed at the end of the Sixties; but that he thinks then, in 1989, is going to come back, though, because history never repeats itself in exactly the same way, it will take a different form.

De Antonio was branded as a communist because of his joining three Marxist organizations when he went to Harvard, precociously, at the age of only sixteen. He had almost been put in a detention camp during WWII because Hoover had been following him since Harvard. (That would have been in 1935.) He avoided detention, and served in the Air Force. Over the following years the FBI assembled ten thousand pages on "De." No wonder when he came to tell the story of his life and declare his principles on film, he called it

Mr. Hoover and I. This is a simple film, without music, without illustrative clips, edited almost in free-association form. But it packs a wallop. This was a man of courage and conviction who made films that matter. I wish I'd known him later, but I'm glad that at least I "met" him, even if the circumstances were unpropitious.

(There is a place

online (among several) where you can watch de Antonio interviewed about

Hoover and I, along with excerpts from the film.)

According to Thomas Waugh,

writing in 1976 ("Beyond verité: Emile de Antonio and the new documentary of the 70s"), "radical saint" was a title given to de Antonio by

Rolling Stone. Waugh was writing on the occasion of a retrospective of de Antonio's "beyond vérité" documentaries at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in that year; de Antonio rejected the claims and mannerisms of "cinéma-vérité." He felt it was obtrusive and doctrinaire, behind a pose of "authenticity" and "realism." In de Antonio's films for the most part he never obtrudes, but his commitment and bias are, by intention, just as frank and starkly evident in documentary compilations like

Point of Order as they are in his autobiographical

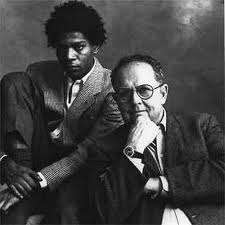

Mr. Hoover and I.  Emile de Antonio with Jean-Michel Basquiat

Emile de Antonio with Jean-Michel BasquiatDe Antonio's first film,

Point or Order (1964, 97 min.) is a 93-minute condensation from over 180 hours of kinoscope TV footage of the 1954 Army McCarthy hearings. These are believed to have spelled the end of Senator Joseph McCarhy's demagogic red baiting. At least they exposed the man's meanness, unprincipled megalomania, and borderline insanity to the American public. The film, a considerable feat of editing, flows seamlessly, including the hearings' key moments and telling a devastating and succinct story without a word of narration. In the DVD of

Point of Order the "commentary" is a sequence of interviews in which de Antonio reveals his wide range of acquaintance with people in politics and journalism and his encyclopedic knowledge of American history and the politics of his time. As he says, the kinoscope footage, originally shown on television and watched by millions (in my family we had no TV but we listened to the hearings on radio), assumes a stature both heroic and grotesque when blown up for the big screen. The film conveys a profound, depressing, and enlightening message. McCarthy, a villain of Shakespearean proportions, with his snide imperial longings and his deep bullying voice, is a terrifying and horrifying figure.

Point of Order is a disturbing watch. But it is also a strangely reassuring illustration of a new kind of American democracy, the democracy of media overexposure doing its cleansing work. De Antonio worked with Daniel Talbot, the immensely influential New Yorker Films distributor of foreign films, who coproduced. All de Antoinio's films made money, but

Point of Order was the most commercially successful of them. It was widely seen and was shown on PBS three times.

De Antonio's next major documentary,

Rush to Judgment (1966, 98 min.), which was made with Mark Lane, a civil lawyer, researcher, and author of a book of the same name, was made closer in time to the events it focuses on, for it concerns the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, only three years earlier, with interviews conducted only a couple of years after the events in Dallas. Kennedy was a classmate of De Antonio's at Harvard. De Antonio did not believe the Warren Report or think that Lee Harvey Oswald killed KFK. He was not sentimental about his classmates, but he felt JFK had been a new kind of president with exciting plans who deserved a true report. He discusses the making of the film in an

interview reproduced on YouTube. In the film Mark Lane interviews purported direct witnesses of the assassination whose testimony was not included in the Warren Report. They saw shots fired from elsewhere than the School Book Depository where Oswald was. Lane and de Antonio mainly sought in the film to show that there was evidence from numerous eyewitnesses that Oswald had not been a lone assassin. In the interview, de Antonio says he thinks the CIA working with right-wing anti-Castro Cubans carried out the assassination, but in the film he avoided speculation, merely attempting to show conservative evidence that the Warren Commission and the Warren Report belong to "the trash bin of history."

In The Year of the Pig (1968, 103 min.), about the Vietnam war from its origins in French colonialism, again like

Point of Order consists of nothing but archival footage, but is a far richer mix of it. There are speakers on all sides, historians, journalists, soldiers, politicians, men of the right and of the left, so there is commentary and exposition, but de Antonio himself does nothing but read one short document off-camera. The film shows how the US gradually escalated from "advisers" to big arms supplies to bombing to all-out war in which many thousands of Americans were killed and the US government told lies and lived with illusions while Ho Chi Minh was seen as the great leader of the country from the beginning and Vietnam was always seen by its people north and south as a single country and the south Vietnamese leaders propped up by the US are shown to have been corrupt and inept puppets. While

Rush to Judgment was just as controversial as, and closer to the events it deals with than,

Point of Order,

In The Year of the Pig is even more explosive, because its devastating exposé of US motives and failures in Vietnam came out when the war was still going on -- and, of course, during the great year of worldwide political protest and revolutionary spirit, 1968. (In some locations screens were vandalized, there were bomb threats, and showings of the film were discontinued.) De Antonio said

In The Year of the Pig was his favorite, and one can see why: it is a distillation of devastating analysis and cool anger that epitomizes the filmmaker's outlook and style. His films are an impressive blend of intellect and passion, commitment and detachment.

The Year of the P{g is much broader in scope than the two previous films, reaching back to France's early colonial involvement in Vietnam (with revealing old footage obtained in France) and chronicling everything from Buddhist priests setting fire to themselves to JFK's speeches to US soldiers beating what they called "gooks." As with

Point of Order but with more challenging material,

In the Year of the Pig is a brilliant and enlightening condensation. It was nominated for an Academy Award for best documentary. The film was co-edited by Hannah Moreinis and the famous New York street photographer Helen Levitt.

Millhouse: A White Comedy (1971, 92 min.), like each of de Antonio's documentaries, goes in a new direction for him, because it's a film biography using archival footage. De Antonio thought it was cruel, while others think it was gentle. Though the progression is not strictly chronological or linear, you get images and information depicting Nixon ("Millhouse" being a deliberately comic misspelling of his middle name, Milhous) from early childhood and youth, when he worked in his father's store, up to the doomed continuation of the Vietnam War, including along the way his use of McCarthyite red-baiting in the Alger Hiss case as a springboard to political notoriety. De went out of his way to get hold of the famous September 1962 "Checkers" speech, in which Nixon, with his wife Pat dutifully sitting over to the side like a wax mannequin, pathetically defends himself against charges of receiving improper campaign donations by listing debts and gifts, including a black and white cocker spaniel. Nixon emerges as an American politician desperate to appear upright and decent, but hollow. There are wonderfully giddy moments of unintentional absurdist comedy. The spectacle of American politics is seen at its most foolish. But this is somehow not really one of the most characteristic or successful of de Antonio's films. For one thing, it was made too soon, and ought to have been held till after Watergate and "Millhouse's" resignation from office. Because so much archival biography has been done on film by now, much of this seems somewhat routine. Of course as is usual with de Antonio, it was well timed as a provocation, however, and deeply annoyed by the obviously comic element of the biography, the administration did its best to debunk and squash it. Yet Nixon is not demonized here. He turns out not to have been bad looking in his youth and to have had a pleasant smile.

Underground (1976, 87 min.) was a sensational film. It was shot clandestinely with Haskell Wexler, the prominent left-leaning cinematographer, and Mary Lampson, who edited. As usual de Antonio knew the right people so when he decided to "go underground" to interview former Weathermen, now Weather Underground, members Billy Ayers, Jeff Jones, Kathy Boudin, Cathy Wilkerson and Bernadine Dohrn, he knew whom to ask, and through an elaborate system out of a spy novel he met the person who could arrange for the five then fugitives to meet with his team in a safe house in southern California. Wexler shoots into a mirror so that we see him full on (as well as Lampson and de Antonio), but only the backs of the five radicals. The FBI was furious at this film's being made. They were hunting for these people, and de Antonio succeeded with little difficulty in having a friendly visit with them. It made the FBI look idiotic. It may be that younger Americans with little knowledge of recent history see no point in this film. What can you understand if you don't know history? The Weather Underground, originally part of the SDS, had carried out a long series of bombings of government installations and the three-day Chicago "Days of Rage" to dramatize opposition to the Vietnam war, unemployment, and other wrongs perpetrated by the government. The explosion and fire of a townhouse at 18 West 11th Street in the West Village in New York, due to unintended detonation of dynamite for a bomb, led to going underground. The technical problem of the film is the faces of the five fugitives can't be shown. Wexler uses the mirror, blurry closeups, and some shots through a gauzy curtain to vary the images, but what saves the film is the earnest but articulate explications of the group's thinking -- however misguided their use of violence, their aims and values are admirable, and the film is obviously sympathetic -- and the many inter-cut clips of Fred Hampton, the Attica uprising, and countless other events to illustrate the contexts. There is an inherent drama in the coup of these people being filmed at this time. Late in the film there is a brief clip of two of the Weathermen interviewing people on the street that shows how even the most ordinary citizens at this moment were responding to the revolutionary spirit of the time. This is a remarkable film and once again, de Antonio did something completely different.

Painters Painting (1972, 116 min.) fits earlier in this sequence, between

Millhouse and

Underground, but stands apart from all the rest, because it's not about politics or the filmmaker at all. It's about New York art. De Antonio was active in this scene himself and knew all the important figures he interviews for the film, who include artists, critics, the dealer Leo Castelli, and the collecting couple the Sculls, museum people, the editor of Art News, and the architect Phllip Johnson, himself a significant collector of Rothko, Newman, and others. De Antonio has said that political people never like this film. As Douglas Kellner explains in "American Art 1945-1970: An Introduction ," an essay included as bonus material with the DVD, "Documentary filmmaker Emile de Antonio was himself an integral part of the New York art scene, promoting and befriending several of the major artists who continued to be close friends. He helped Andy Warhol get started in painting, was an early promoter of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, was very close to Frank Stella, and knew personally many of the painters involved in Geldzahler's New York Metropolitan Musuem retrospective of 'American Painting and Sculpture --1940-1970,' upon which

Painter's Painting is based." Is it based on that? Well, it does discuss several artists not directly heard from but significant, such as Hans Hofmann and Jackson Pollack. The critics (whom Barnett Newman calls "aesthetes") come across as arrogant asses here, but Leo Castelli seems simply an urbane pragmatist who found artists whose work he liked and successfully promoted them. Though he may bend the facts a bit in recounting how he got this or that artist started, the collector Robert Scull is sympathetic -- and an essential part of the equation. In the TV interview in which he sums up each of his films, De Antonio argues that art has always been about money, and that critics, dealers, and collectors are essential to the world of art. The buyers may not be admirable, but the artist are doing exciting work are. This film is a bit choppy and some of the sound in the interviews is terrible, but that's worth putting up with for the chance the film provides us to see and here the likes of Willem De Kooning, Newman, Helen Frankenthaler, Robert Motherwell, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland, Andy Warhol, and others, as well as critics Clement Greenberg, Hilton Kramer and other important figures in the New York art world of 1970 and the several decades before. This was after all a time when New York was supreme, lines far more clearly drawn than later, between mattered and what didn't, between abstract expressionism, minimalism, pop, and so on. De Antonio records it as an insider, so again he has provided a unique document of a significant moment -- this time not in political, but cultural history. And it rounds out my partial survey of "De's" oeuvre nicely also because it has a personal significance to me: I grew up as an aspiring artist when the New York School was becoming hot, and Willem De Kooning was the first artist whose process as depicted in

Art News' series "Paints a Painting" first electrified me with its boldness and surprises. To think that De Antonio was there when this stuff was happening!